A great article I found on the vine about live music promoters and Hip Hop artists

A great article I found on the vine about live music promoters and Hip Hop artists

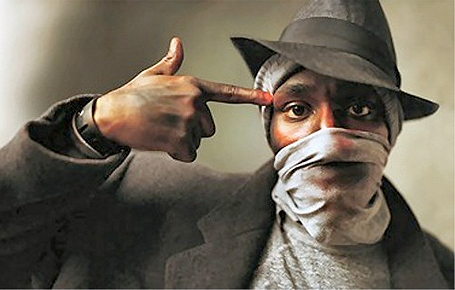

One year ago, acclaimed American hip-hop artist Dante Smith – stage name Mos Def (pictured) – was set to tour Australia for the first time. Eleven shows were booked, including headline festival appearances at Soundscape in Hobart and The Hot Barbeque in Melbourne. After failing to appear at his first scheduled performance in Adelaide, he went on to randomly skip four shows of the itinerary. Such was the ensuing confusion, that following the postponements, cancellations and sternly-worded press releases from the promoter, Peace Music, became something of a sport here at TheVine. For background, revisit our news story ‘Mos Def gone missing on Australian tour’. (I’m pleased to note that he made it to Brisbane for his Australia Day show, which was actually pretty great.)

What did those four cancellations mean for Peace Music, though? The promoters were awfully quiet for the remainder of the year, which posed the question: "Did the Mos Def debacle put an end to their live music interests?". In late 2011, I contacted the company’s managing director, Sam Speaight, requesting an interview about the logistics of touring American hip-hop artists in Australia. “I’d love to do this,” he replied via email. “So often promoters are dragged into the street and shot (proverbially speaking) by the ticket-buying public over hip-hop artists’ cancellations and their childlike antics. Few people understand that, in many cases, the promoters have driven themselves to the brink of sanity and financial ruin to avoid an artist cancelling.”

A couple of days later, we connected via Skype. “The total chaos that seems to govern most of all the management side of these artists’ careers is just dumbfounding,” Sam told me from his new pad in London. “If people knew what went on behind the scenes, if nothing else, it would be a spectacle worth reading about.” He’s not wrong.

AM: Tell me about the Mos Def tour, Sam. Was this your worst experience with touring hip-hop artists in Australia?

SS: Oh, yeah. That was definitely the worst example of madness and insanity from an international artist that I’ve ever seen, or heard of. Utter madness permeated everything that happened, in terms of the artist’s management, the delivery and management of the artist’s live engagement. He’s since pulled similar things at the Montreaux Jazz Festival. They’ve just gone through a similar experience to what I did, but fortunately, they only had one show to deal with, whereas I had an entire headlining tour.

Let’s go back to the start. When you first confirmed the booking, was there a point at which you realised that things might not go to plan? Were alarm bells ringing at any point during the lead-up to his arrival in Australia?

Good Lord, yes. Even before I signed the contract with his “management”, in inverted commas, I was aware that this was a difficult, tricky, potentially trouble-fraught artist to deal with. I structured as best I could my strategy for dealing with this artist to minimise the potentiality for misadventure in the establishment phase of that project. But all the pre-planning in the world couldn’t have prepared me for the living nightmare that was the reality of doing that tour and dealing with Mos Def. [Laughs] I literally broke down and cried partway through the tour.

You need to set the scene. Where were you when you broke down and cried?

[Laughs] I was at home. It was a Sunday afternoon, if I recall correctly, at my house in Redfern – which I’ve now sold, by the way. I’ve moved to the other side of the world to try and forget all about this experience! [laughs].

I was at home, hanging out with my lovely girlfriend, Gillian. Earlier in the day, Mos’ tour manager had called to advise that the rescheduled make-up show, which had been put in place in connection with one of the shows that he’d cancelled on his tour – the Tasmanian show. He advised that the make-up show would not be going ahead, and they would be unable to play it. Which was a disaster. One of a string of disasters that occurred on that tour. I was in an awful state of mind as a result of that, because it meant yet more massive financial losses, and yet more damage to my company’s name and reputation insofar as I was delivering the show to a promoter in Tasmania, I wasn’t promoting it myself. So there was a third party affected by this madness.

A few hours after I dealt with that disaster, I got a call from my tour manager, to say that he’d been asked a question via [Mos Def’s] managers, the question being: “Are there any other shows that we can play on this tour? Can you please investigate booking us some more shows? We would like to try and play some more shows.”

This is three or four days before the end of the tour. I remember reaching this psychological breaking point, where I’d been assaulted by this emotional nightmare every day for a month, in the lead-up to the rescheduling of, then delivery of this project. I said to my tour manager, “I can’t believe you’ve just asked me that question. You know how much money I’ve lost here. You know that the tour’s four days from completion. Are you totally insane? Who in the southern hemisphere is ever going to book this artist ever again? After what’s gone down here, for a start. And further to that, how on earth would I be able to organise any new shows within the space of four days given the fact that I’m staring down the barrel of financial ruination?”

That was basically just what tipped me over the edge. I just remember being in my living room, just losing the plot. It was the straw that broke the camel’s back! [laughs]

But it gives you an insight into just how warped and twisted, and how absolutely separated from reality the awareness of management – within the scope of that being a professional function – is, in the minds of these artists. They seem to live in such a bizarre, self-constructed reality that is so far away from what you might describe as career management, business, or just basic logic. [Laughs] Their worldview and outlook… it’s difficult for people like me — and I assume like you, too — to understand people who have to justify their existence by earning a dollar, which is then pursuant to them doing a good job of things, and being a professional. This is just a world that a lot of these people seem to be able to avoid living in.

And Mos Def’s a great example. If you Google, you’ll see that in the last 12 months there’s been a spate of these absolute last-minute cancellations. If the cancellation or postponement is done in a way that allows the promoter some opportunity to minimise their losses and to at least deal with the ticket buying public in a professional fashion, so that it doesn’t damage that artist’s fanbase and the promoter’s business, then cancellations are unfortunately sometimes a part of doing business in the music industry. But that’s not the approach that’s usually taken in these situations by these American hip-hop artists. More often than not, there’s very little justification if any given for it. It’s oftentimes just a childish whim, whereby they’ve decided that something about the project isn’t to their liking, or they’ve got something better to do that day, or they don’t feel like getting out of bed that morning.

As a result of that, they’re perfectly happy to – in some promoters’ cases – turn people’s lives upside down, and

send peoples’ whole businesses spiralling toward the ground without any thought for basic humanity.

This is probably a long bow to draw, but I see a lot of this same attitude toward happily disregarding other people within the scope of business, and totally ignoring the massive financial ramifications of doing something like cancelling a show 24 hours out, to the problems we’re seeing across the entire global financial system at the moment. You’re basically talking about an approach to doing business that is morally bankrupt. It’s the exact same underpinning ideology that I see caught up in the actions of Goldman Sachs, and Bank of America, whereby these people are perfectly happy, without a single qualm in the world, to destroy peoples’ lives, trash peoples’ businesses, send people broke, without even a second thought. Just as long as – whatever they decided to do that day, gets done. I think that’s what really drives at this. The financial system that these people are participating in, and their actions, by association and as a function of that system, are absolutely and utterly morally bankrupt. But that’s a very long view, I guess. [Laughs]

You mentioned earlier that, with Mos Def, you were dealing with a “difficult, tricky” artist. What exactly do you mean by that? What were the warning flags that you saw, or heard?

I mean that, when I plugged the words ‘Mos Def’ and ‘cancel’ into Google, there were a number of different results that came up; ie he’d cancelled other shows in the past. His compulsion toward cancellations seems to have increased a lot in the last 12-18 months. I’ve seen a lot of these issues arise. I know that there’s another issue at play at the moment with Live Nation. I don’t know the specifics, but I’ve heard through the industry grapevine that there’s been a similar situation go down with a Live Nation show recently, and that’s created a lot of negativity and fall-out.

But look, anybody who deals with US hip-hop artists, they’re — by the very nature of what they’re doing — dealing with a high risk business model. I’d like to think that, up until the start of this year, I’ve specialised in delivering these US hip-hop artists. I’ve directly involved in managing, delivering and promoting shows for Public Enemy, Method Man, Redman, Lupe Fiasco, De La Soul; all sorts of different international hip-hop artists. I like to think that I’ve developed a system for ensuring that these projects are delivered successfully, and that they don’t cancel. And, touch wood, prior to Mos Def, I’d only really had one serious disaster go down, in terms of a total cancellation. I thought to myself, “I’m used to dealing with these artists, I’m going to strategise this as best I can. I’m going to incentivise it for the artists as much as I possibly can, and deal with it in the most professional way possible.” I looked at my track record and went, “I can do this.” And I was wrong! [Laughs]

Who was the other cancellation?

Other cancellation was Phife Dog and Ali Shaheed Muhammed from A Tribe Called Quest [ATCQ]. I was involved in co-promoting the incredibly successful debut ATCQ tour in the middle of last year. During the lead-up to the tour, I got to know Phife and Ali’s managers. I was in contact with their reps before the ATCQ tour became an opportunity. That [situation] was the direct result of their agent banking a bunch of tour deposits and running away with the money. It was done in collusion with an accounting firm here in the UK; what would appear outwardly to be a very reputable accounting firm called [redacted]. They’re like a hundred year old law firm, but the managing director had basically teamed up with this guy to create a smokescreen of legitimacy around what he was doing, in order to steal my money. I went as far as calling the MD of this company, sending him contracts, speaking on the phone, confirming the details with him in writing on email, had a paper trail 10 miles long. When it all came to pass, and I finally realised I’d been duped, I called him and said, “Mate, what the hell’s going on here?”. He said, “Who are you? Why are you calling me? I don’t know you. Sorry. Bye.”

Wow.

There’s a total lack of management expertise anywhere in this end of the industry. This is the immediate reason that drives these outcomes. The people managing these artists couldn’t manage a bet in a casino, you know? Most of the time they’re friends. Very rarely are they reputable managers. A lot of music industry managers are friends, I guess. This isn’t uncommon in the entertainment business. But there’s a culture of doing business in a very haphazard and sloppy fashion that permeates the US hip-hop world. That shines through when you’ve got a manager who isn’t qualified, and also isn’t expected to do a good job. So they don’t.

Of course that’s a broad brush stroke; I don’t want to paint every hip-hop manager with that. Conversely to my experience with Mos Def, I’ve done five Australian tours with De La Soul. Their manager is an absolute dream to work with. He’s an incredibly diligent, focused guy who does an amazing job of managing his clients to get results. Unfortunately he’s the exception as opposed to the rule.

You’re saying that your business is inherently risky, in that you’re touring some of the most volatile artists in the world, yet up until Mos Def you’d managed that risk quite well.

Yeah. Even the Phife Dog scenario – it was a small loss. Around $10,000-12,000, if I recall correctly. Within the scope of my business, it was irritating, annoying and upsetting – and a blow to my ego – but it wasn’t a disaster that brought the walls of reality crashing down. But through a combination of luck and very hard work, up until Mos, I’d managed to avoid any misadventure with any hip-hop artist I’d toured previously, and I’d done it for a good five years prior to Mos Def.

But I need to talk in the past tense now. I have stopped touring these US hip-hop artists. I’m still in touch with one or two of my old clients who are managed by reputable, well-resourced management companies, and managers. But I’m completely done with working with any artists in that sphere at all. [laughs] I’m done with it, basically.

Does that mean that you’re selling Peace Music? Or are you shutting it down?

That’s not determined right now. We’re still working on maintaining Peace Music to some degree, but my days as a concert promoter are almost over. I’m in the final stages of starting a new technology business, which delivers digital solutions to the entertainment industry. That company is an absolute departure from the live entertainment industry. Very soon I’ll be able to turn my back on that industry for good, and wave it goodbye, thankfully and happily. I’m also about to commence an MBA at Cass Business School, the second highest-rated business school in Europe. So what I’m doing here in London is a total revamp of my entire career. Will I stop doing business wholly and forever in the live music industry? I don’t know. But certainly my view at the moment is fixed firmly on a very different cross-section of the industry.

I want to clarify a few things about Mos Def. I know it’s painful to revisit, and I appreciate that you’re humouring me as much you are.

No, it’s fine. Looking back on it now… I’m a bit of a hippie, a bit of a Buddhist. I believe that everything in this life has some kind of underlying karmic reason behind it. I was meant to have that experience. I’ve had it now, and as awful as it was, I don’t regret it. It’s part of my path here, on this plane. [Laughs]

That’s a good view to have.

Thank you. [Laughs]

So how many shows did Mos Def show up and play?

From memory, he cancelled four out of 11 shows. We got away with about two-thirds of the shows that he’d said he’d play.

What did those four cancellations mean for your business?

Those cancellations meant an immediate net loss of around $250,000.

Holy shit.

To put things in perspective… let’s look at the Melbourne show [at The Palace] as a singular example. After having rescheduled the entire tour once – some of the shows had been rescheduled twice – and after having postponed airfares, and booked new airfares about six different times, and incurred a huge amount of costs and cancellation fees… I got a call at 5am on a Saturday, two hours before they were due to book their flight to Australia, to tell me that they wouldn’t be getting on the flight because one of the manager’s daughters had slipped and hit her head on the ground, and that as a result, the tour couldn’t commence.

This is after weeks of mind-crushing madness and insanity that wore me down to breaking. That was Saturday morning. They were originally supposed to board flights on Friday, but they refused and postponed. So the daughter had hit her head, and they couldn’t come. You know, this is just ridiculous; the manager with the daughter was completely non-essential to the tour.

So that was at about 5am on Satutday. At 9am, I began calling The Palace in Melbourne, and also my ticketing company, Ticketmaster. The show was due to take place on the following day, so we literally had about 28-30 hours advance warning. I finally got through to someone a bit before midday — which is perfectly reasonable for a company that operates a 9-5 business — the guys at Ticketmaster just said to me, “Sam, there’s no way we can postpone this show. We can’t contact all the ticketholders. We don’t have enough staff in the office today to call people even if we could try to do that. The only option you’ve got in this scenario, I’m sorry to say, is to cancel the show and refund all the money that the ticketholders have paid.”

So that was revenue that I was counting on to pay the enormous mounting bill that had already been accumulated through the various cancellations and re-booking of airfares across the tour. And then all of my marketing, production and delivery costs, and hotel bookings – all that money just went straight down the toilet. The Melbourne show was sold out; the tickets were roughly $80. So just that one cancellation represented a wrecking ball to the foundation of my business. If you apply similar thinking to the other shows across the tour, you quickly begin to comprehend the scope of the damage that those cancellations resulted in.

What about the artist fee? Tell me about the contract. Did you have clauses for cancellations? Did you pay the fee upfront?

We absolutely had bulletproof, watertight contracts in place with the artist. They were breached… God, I lost track of the number of contract breaches in the end, to be honest. But unfortunately a contract is only as good as one’s willingness to go to court to prosecute it. If you’re not willing to put your hand in your pocket and go to court to get your money, then you might as well scribble some incoherent lines on the back of a napkin and exchange that with your client, and call that your contract.

In the end, the contract was basically meaningless. It was breached so many times that, in the end, I forgot all about using it as a legal instrument, because it quickly became apparent that, at the end of this tour, I wasn’t going to have enough money to buy my next meal, let alone…well, I use that in a dramatic sense. [Laughs] Obviously I’m not a pauper living in the streets.

But it was immediately apparent well before he got on the plane that I was not going to have the money to go to the US and fight a court case there to get my money back. I still haven’t done that, primarily because of my Buddhist leanings. I believe that this was an experience I was supposed to have. I have to experience it, let it go, move on, revamp my entire approach to everything that I do in my life, move halfway around the world, sell my worldly possessions, and completely start again. [laughs] So instead of going to court – that’s what I did.

So not a big change, then.

Just a small change, mate. Business school…[laughs].

Look, if I wanted to, if I had the money, the time and the inclination, I could take him to court, but I don’t want to. I don’t have the desire to do so. In life, oftentimes it’s better just to move on, understand that you were supposed to have that experience, and learn and grow from it. Yeah.

How do you feel about Mos Def now? Can you listen to his music? Can you go anywhere near that name?

Well, no. I don’t listen to his music anymore, no. [laughs] I was once upon a time a fan, but no longer. Look, again, because of my Buddhist leanings, I don’t bear Mos Def any ill will anymore. I did for a few months there. I was very upset. But I’ve come to understand that, like all things in life, this was an important part of the path that I’m here to walk. I have done all I possibly can to let go to the negativity that was contained in that situation, as I believe that by hanging onto it, you run the risk of it happening again. I look at it as a fatalistic part of my karma.

That’s very mature.

Thank you very much. Look, Dante – Mos Def – he’s a very strange artist who operates in very strange ways that I don’t understand, but in the end, he’s another human being doing what he does, and I bear him no ill will.

So Mos Def, your reaction to this article please